Western Gorilla Tourism

Categories: Tourism, Journal no. 38, Behaviour, Other countries, Other protected areas, Western Lowland Gorilla, Gorilla Journal

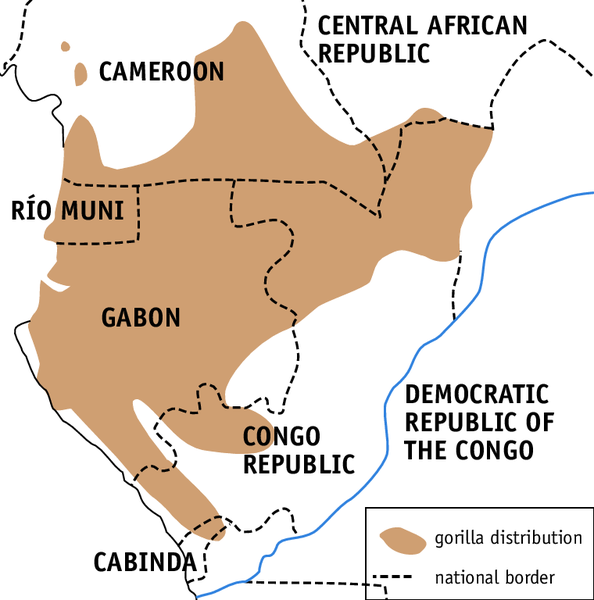

Following the widely perceived success of mountain gorilla tourism, there has been increasing interest in developing tourism based on the observation of western lowland gorillas. The difficulty in habituating western lowland gorillas to human presence has limited the number of sites, restricting tourist and film crew visits to a handful of gorilla groups. This preliminary study is the first to evaluate the impact of such visits on western lowland gorilla behaviour. We focus on the impact of visitor number, distance and type (tourist/film crew/researcher/tracker) on the short-term behavioural responses of a western lowland gorilla group at Bai Hokou, Central African Republic.

The Bai Hokou gorilla tourism program was established in 1998 as part of the Dzanga-Sangha Project: an integrated conservation and development project, run in partnership between the Central African Republic government, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the German Technical Cooperation (GTZ). Following 4 years of intensive habituation efforts, the program was opened to tourists in 2002. In contrast to mountain gorilla tourism, this program is still run on a relatively small scale. There is currently one habituated gorilla group visited by a maximum of 3 tourists at a time (although two tourist groups may visit the gorillas per day). A further two groups are in the process of being habituated for the same purpose. As home to one of the few habituated western lowland gorilla groups, Bai Hokou also frequently plays host to film crews and independent researchers.

This study was designed to assess the effect of human group type (research/tourist/film crew) and size on gorilla behaviour. We collected behavioural data during visits to group Makumba, which, during the course of the study, was composed of 1 silverback, 3-4 females, 4 juveniles and 4-5 infants. Data were collected over a 12-month period beginning November 2005 in the presence of tourist groups, film crew groups and researchers and trackers only. Analysis focused on the effect of human type, number and distance on gorilla behaviour, here measured in terms of activity budget, frequency of aggressive behaviour and vocalization, and silverback close calls and long calls.

Since program inception in January 2002, visitor numbers have steadily increased to around 300 tourists per year, with tourists experiencing an average of 69 minutes' unobstructed visibility of the gorillas (although tourists may spend more time in the area with visibility obstructed by thick vegetation). Over the 12 months of this study, we recorded data on 98 separate days. This included 25 days' observation accompanying tourists or film crews. During the study period an average of 2.6 trackers and 1.7 researchers visited the gorillas each day. Tourist/filming groups ranged in size from 1 to the project maximum of 3 tourists/film crew members. Tourist group size average over the study period was 2.0 people.

The amount of time the silverback was in view was found to be strongly related to the type of visitor group, with those including film crew significantly more likely to see the silverback than those just containing researchers. We also found that the visibility of the silverback was positively related to the number of tourists and negatively linked to the number of researchers. The number of film crew members had no effect.

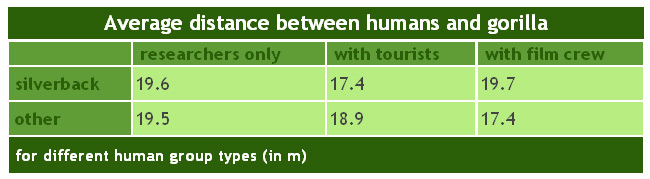

Serious concerns have been raised regarding the possibility of close contact between humans and wild gorillas and the related health risks (e.g. Wallis & Lee, 1999; Woodford et al. 2002). Whilst our data suggest that tourist groups do tend to get closer to the gorillas when compared to visits by just trackers and researchers, all averages well exceed the project-set minimum distance of 7 m.

We also found that more tourists resulted in a smaller distance between the tourist group and both the silverback and other group members.

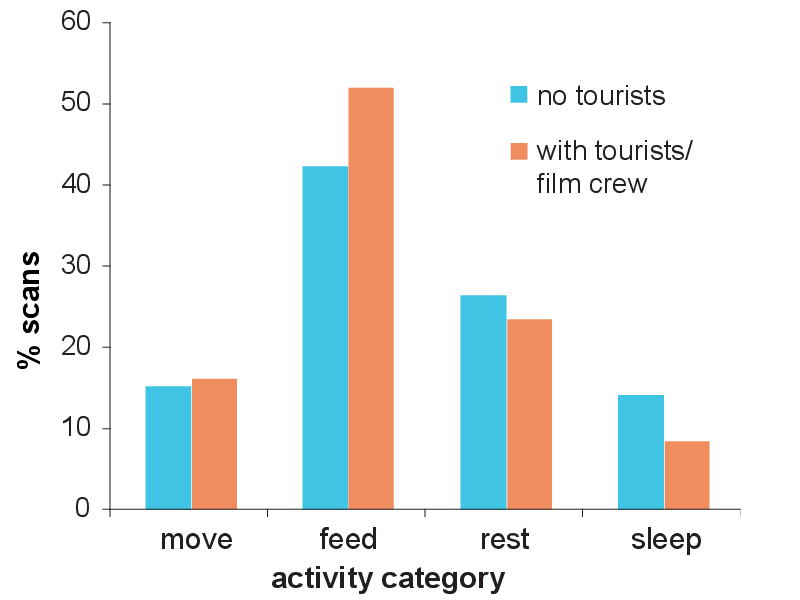

Gorilla activity budget when in the presence of tourists or film crew was not found to be significantly different so data were combined for ease of analysis. The presence of tourists/film crew was found to have an effect on silverback activity, causing him to spend less time resting or sleeping and more time feeding. Increasing the total number of humans present resulted in a similar effect.

Incidences of aggressive vocalizations and behaviour were generally low. 6% of the 10-minute long observation periods featured an aggressive vocalization or behaviour from the silverback, the most common of which was a bark or soft bark; 4% featured an aggressive vocalisation or behaviour from another group member - usually a bark or soft bark by a female. The presence of film crews resulted in an increased rate of aggressive vocalizations by the silverback compared to when in the presence of just trackers and researchers, and increased group aggressive behaviour when compared to both tourist groups and non tourist groups. The silverback was also found to emit significantly more belch vocalizations in the presence of film crews than he did with either tourist groups or research groups.

The economic success of the mountain gorilla tourism programs has led to an increasing interest in habituating western lowland gorillas for that purpose. This study is the first to evaluate how the type and number of humans affects the short-term behaviour of western lowland gorillas. These results show that, far from being accepted as a neutral element in the environment, the presence of film crews, tourist groups, and even an increased number of researchers, can alter gorilla behaviour.

The presence of film crews appears linked to increased rates of feeding at the cost of resting or sleeping, higher rates of silverback close calls and silverback aggressive vocalizations, and increased rates of group aggressive behaviour. Film crews were also found to spend significantly more time in visual contact with the silverback. This evidence of both increased time spent in close proximity to the silverback, and the impact on his behaviour, is unsurprising when considering the pressure film crews are often under to gain quality footage under difficult conditions and often strict time constraints. Closer following of the gorillas, along with constant shifting of position to obtain higher levels of visibility, have the potential to create greater disturbance amongst the gorillas. Furthermore, the considerable amount of equipment that film crews require greatly increases the amount of noise generated while tracking and viewing the gorillas. Whilst the level of disturbance witnessed nevertheless appears generally low, these results should be considered a warning as to the potential for film crews, often engaged in actively promoting gorilla conservation efforts through film, to actually negatively impact the gorillas in question, highlighting the need for careful management.

The presence of tourist groups was found to be linked to increased incidences of aggressive group behaviour and increased rates of feeding at the cost of sleeping and resting in the silverback. Tourist group size also affected both silverback visibility and distance, with larger tourist groups achieving greater visibility at closer distances. Researchers should also consider the effect of their presence on gorilla behaviour, with an increasing number of researchers shown to be linked to alterations in activity budget.

Despite the changes in gorilla behaviour in the presence of different visitor types, levels of aggression and activity budget changes remained relatively low. Lowland gorilla tourism, when compared to mountain gorilla tourism, continues to operate on a much smaller scale. The level of habituation of Makumba group means much greater distances are maintained than with mountain gorillas (Sandbrook & Semple 2006). Given the density of vegetation in the area, visibility at these distances is often limited and, as a result, tourist groups are deliberately kept smaller - a maximum of 3 people as compared to 8 - to try and ensure each tourist gets a rewarding view of the gorillas. Nevertheless, from the ecological viewpoint what we are ultimately interested in is how these short-term behavioural changes relate to long-term effects, in particular group demographics. Such impacts will take longer to be revealed, although it is interesting to note that the group's females have been successfully reproducing during the 7 years since habituation began, and most have given birth to two or three infants during this time. The disease risk posed by the tourists, to both the visited gorillas and other, unhabituated groups, also remains unquantified (to be assessed).

The levels of visibility and tourist satisfaction with tracking group Makumba at Dzanga Sangha (Hodgkinson et al. in prep.) shows that, sensitively managed, western lowland gorilla tourism programs are feasible. They may remain limited, however, by continuing issues such as the political instability of the host countries and the difficulties and high costs associated with accessing the site.

The difficulties involved in "habituating" lowland gorilla groups to the level at which it is possible to take visits should not be underestimated - it is a process which takes years of hard work, and the support of experienced BaAka trackers has been crucial to habituation attempts. Gorilla habituation can also be extremely costly, with a considerable financial investment required to both develop and manage the program, often in very remote locations.

Furthermore, by training wild gorillas to lose their fear of humans, we are potentially putting them at increased risk of hunting. It is therefore crucial that long-term funding be secured to ensure the continued protection of habituated groups. Finally, managers should be wary of basing a tourism program on just one group. The disbanding of another habituated gorilla group in 2004 caused the temporary closure of the tourism program in Dzanga-Sangha.

Chloe Hodgkinson and Chloé Cipolletta

We are greatly indebted to the Dzanga-Sangha project and staff for their assistance throughout this study, made possible through the support of the Central African Government and the World Wide Fund for Nature. Particular thanks must go to the guides, trackers and volunteers at Bai Hokou camp. Grateful acknowledgment of funding is due to both Natural Environment Research council and the Economic and Social Research Council.

References

Sandbrook, C. & Semple, S. (2006) The rules and the reality of mountain gorilla Gorilla beringei beringei tracking: How close do tourists get? Oryx 40 (4), 428-433

Wallis, J. & Lee, D. R. (1999) Primate Conservation: The Prevention of Disease Transmission. International Journal of Primatology 20, 803-826

Woodford, M. H. et al. (2002) Habituating the Great Apes: The Disease Risks. Oryx 36, 153-160