Moukalaba-Doudou

Categories: Gorilla Journal, Journal no. 38, Tourism, Behaviour, Other countries, Other protected areas, Western Lowland Gorilla

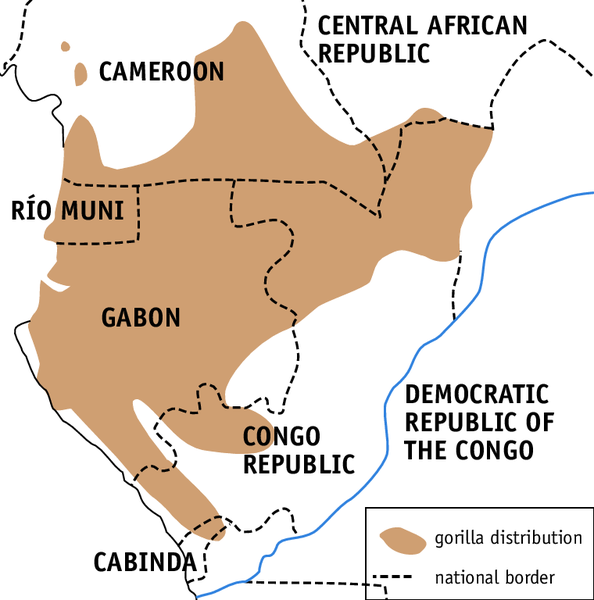

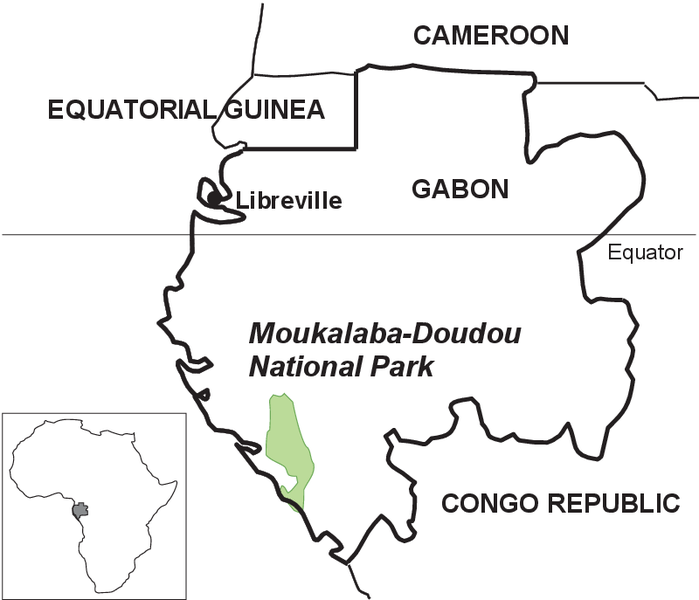

Since 1999, a long-term survey of gorillas and chimpanzees has been conducted by Kyoto University in Moukalaba-Doudou National Park, Gabon. The Moukalaba area was gazetted as a forest reserve in 1962 and as a national park in 2002. Selective logging was carried out from 1962 until 1988 by a logging company. Although local people living near the park say that gorillas had been hunted in this period, we find no evidence of hunting of gorillas and chimpanzees at present.

The Moukalaba-Doudou National Park is located about 700 km south of Gabon's capital, Libreville, and covers 5,028 km², and our study site is located on the southwest side of the park, covering an area of about 30 km². The study site is roughly divided into four vegetation types: old secondary forest, riverine forest, young secondary forest (ancient plantation of Musanga cecropioides, and Aframomum sp. are dominant), and savanna. There are two seasons: a rainy season from October to April and dry season from May to September. Annual rainfall in the study area fluctuated from 1,582 to 1,886 mm for three years (2004-2006), and mean monthly minimum and maximum temperature ranged from 21.3 to 24.1 °C, and 29.3 to 33.7 °C, respectively.

We form a research team consisting of researchers and field assistants to follow the daily fresh trails of gorillas and chimpanzees, recording their travel routes and collecting fecal samples, in order to analyze their diet and ranging patterns. In 2003 we focused on habituating gorillas to understand their social ecology. In other study sites, hunter-gatherers are usually employed as trackers, because of their skill at tracking wild animals in the tropical forests (Tutin & Fernandez 1991; Cipolletta 2003; Doran-Sheehy et al. 2007); in our case, we employed local farmers as field assistants, because there are no hunter-gatherers living in the areas around the park, and it is very important for local people who live around the park to get a chance to work and to understand and carry out wildlife conservation. In the first year we employed about 16 local people from three villages, Doussala, Konzi and Mboungou, who wanted to work with us. The following year we selected seven people who had high tracking skills and who were motivated.

In January 2004, we identified one group of gorillas named Group Gentil (GG) for habituation, but it was still difficult to follow them constantly. In November 2005 we concentrated on following only GG, and since then we have contacted them on a daily basis. By July 2007, we had succeeded in following the group continuously between consecutive nest sites, and we have gradually increased contact time with them. It took 21 months for us to achieve all-day follows.

The group consisted of a silverback male, a blackback male, 9 females, 6 suckling infants, and 5 juveniles/subadults in January 2008. Two females left the group between February and May 2008, and another female left in July 2008, hence the group's size was 19 individuals as of August 2008. By June 2008 we had indentified all group members and named them.

The responses of the gorillas in GG to human observers changed over time as habituation progressed, and their responses varied with sex and age. At first, almost all gorillas ran away when they encountered the observers. In September 2006, when the number of contact days increased rapidly, the silverback started to threaten us and sometimes made mock-charges. Almost all adult females avoided the observers, and it was difficult to see them during this period. Once all-day follows were achieved, the silverback started tolerating our approaches, and the infants showed great interest in our presence, but several females showed aggressive behaviour such as slapping tree trunks, chest-beating and screaming persistently, frequently making mock-charges toward observers, and they occasionally bit us. The silverback, therefore, was more quickly habituated than the females.

Such female aggression never has been reported in the process of habituation of mountain gorillas and eastern gorillas. Doran-Sheehy et al. (2007) reported similar female aggression in encounters with observers during the process of habituation at Mondika, although the responses of silverback males to female aggression are different between Mondika and Moukalaba. At Mondika the silverback rarely joined in the females' attacks on human observers and mostly ignored them, even if the females attempted to enlist his support; at Moukalaba, by contrast, the silverback rushed at females who attacked us with aggressive vocalisations and probably stopped them by grasping or pulling them down on the ground. These observations suggest variations in social relations among group members between gorillas in different habitats, although we need more observational data on their social interactions in agonistic contexts before interpreting such variations.

We can make the following conclusion regarding the habituation of western lowland gorillas: the first important task is to train good trackers. Our experience shows that even inexperienced trackers increased their skill to attain reliable follows of wild gorillas under the difficult conditions of the tropical forests of Central Africa. Secondly, successful habituation needs constant contact with the same single group, tracking their movements, and increasing the frequency of contact and the duration of contact time with the gorilla group.

To enhance our efforts as far as the conservation of wildlife, including gorillas, is concerned, we named all individuals in GG in consultation with our field assistants, and tried to familiarize these names with local villagers; and we employed men and women from villages near the park, as many as possible, not only as trackers but also for other simple work, as we wanted to give local people the opportunity to earn money - in this way, the people can better understand our activities and the importance of wildlife conservation. In addition, the research team and local staff coordinated the first cinema show for all villagers in Doussala in December 2007 and January 2008; in this show we introduced our research work and showed a gorilla video, and we found that some villagers were seeing wild gorillas for the first time in their lives, even though they live near the habitat of gorillas. Because of these shows, gorillas became popular in all villages, and conservation awareness and activities increased among local people.

Chieko Ando

References

Cipolletta, C. (2003) Ranging patterns of a western lowland gorilla group during habituation to humans in the Dzanga-Ndoki National Park, Central African Republic. International Journal of Primatology 24, 1207-1226

Doran-Sheehy, D. M. et al. (2007) Habituation of western gorillas: The process and factors that influence it. American Journal of Primatology 69, 1354-1369

Tutin, C. E. G. & Fernandez, M. (1991) Responses of wild chimpanzees and gorillas to arrival of primatologists: Behaviour observed during habituation. Pp. 187-196 in: Box, H. O. (ed.) Primate responses to environmental change. London (Chapman & Hall)