The Power of Local Stories in Lebialem, Cameroon

Categories: Gorilla Journal, Journal no. 37, Conflicts, Cameroon, Tofala Hills (Bechati-Fossimondi-Besali), Cross River Gorilla

Cross River gorillas are found in isolated forest blocks including the Bechati-Fossimondi-Besali forest area in Lebialem Division, southwest Cameroon. Current threats to their exist-ence in this area include hunting, forest conversion into farmland, and habitat fragmentation. The Bechati-Fossimondi-Besali forest (80-100 km²) rises from about 500 m in Bechati through 1,700 m at Bamumbu to 1,900 m in Fossimondi (Oates et al. 2007). Topographically it consists of a series of hills and mountains with steep slopes and deep valleys. The change of vegetation from lowland to lower montane forest gives rise to a high level of plant and animal biodiversity. This challenging topography has limited the potential for commercial logging. However, a logging concession is located some 5 km from Bechati and currently under exploitation (Nkembi et al. 2006).

This study was conducted in 5 villages (Bechati, Besali, Fossimondi, Bamumbu and Folepi) to document stories told by local people about Cross River gorillas and assess the power and influence of these stories to people's values and perception towards gorillas both in rural communities where they are told, and in urban centers that have a greater outside influence. For centuries, stories of this nature have promoted cultural and behavioural norms of traditional African societies, and such oral traditions are the only means through which knowledge and wisdom about the environment is passed-on and sustained from generation to generation (Jacobson et al. 2006). These stories, when retold in their origin-communities or to indigenes of these communities living in urban areas, could contribute significantly to influencing people's value systems and restore their kinship with nature's creatures (Rose et al. 2003). In addition, tales of myths about wildlife provide an excellent means of breaking tradi-cultural barriers and obtaining community recognition of conservation education programs.

The Bechati-Fossimondi-Besali forest is not protected by government and hence is communal land (Nkembi et al. 2006). In such community-owned forest regions, informal institutions and traditional practices such as local tales and taboos, guided by cultural norms, can play an active role in nature conservation. In these areas it is social norms, rather than governmental juridical laws and rules, that determine human behaviour. People do not disregard taboos against hunting gorillas because, if they do, they may be punished by the ancestors or traditional institutions, unlike the wildlife law which is either poorly understood or hardly recognized. Taboos represent unwritten social rules that regulate human behaviour. Unfortunately, social institutions such as taboos, myths and wildlife tales are always neglected in conservation design (Colding & Folke 2001), although areas with high biodiversity in developing countries are always associated with regions of high traditional value systems.

The population of the five villages surveyed is estimated at 15,000 (2006). Farming, hunting and trapping are the major livelihood activities. Local oil production is a booming agricultural activity in the area and plays an important role in daily sustenance. Women, who are regarded as assets of men (some refer to their wives as having been "bought"), collect non-wood forest products and sell them in local markets in addition to crop farming, to support the income brought home by their husbands. Hunting is more severe in Bamumbu than other communities due to lack of alternative skills to engage in more profitable and off-forest enterprises. Birth rates are very high in this area.

Throughout the region social facilities such as pharmacies, health clinics, electricity, and piped water are absent. People rely heavily on traditional healers for their healthcare. Political authority is vested in a village chief, who is supported by a council of elders. Social behaviour within the village is further controlled through a series of extensive age-grade associations and secret societies, both of which fall under the auspices of the village chief. The government works through these village structures to govern the people and the decisions of the chief or traditional council are highly respected.

Methodology

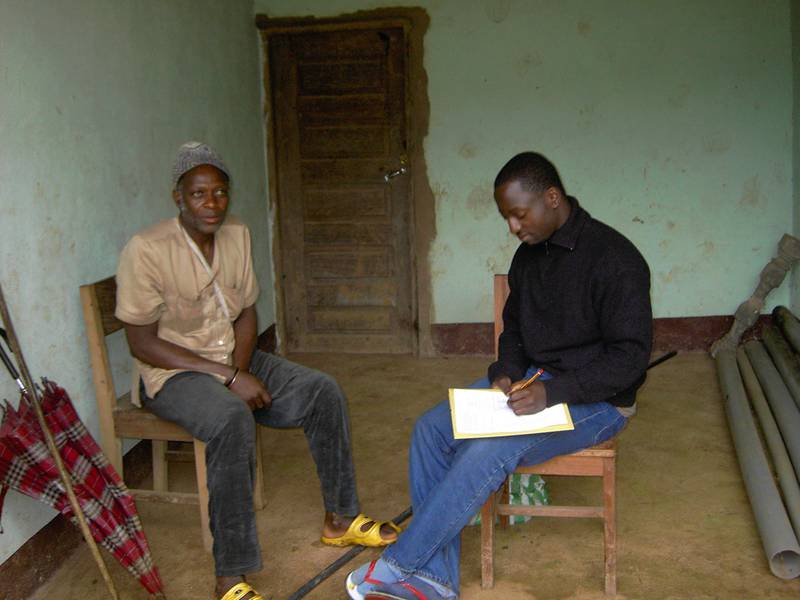

During a 2-week stay in forest communities in Lebialem Division, South West Cameroon, we collected stories of myths, totemic kinship, physical encounters, hunting, rituals, and eating of gorillas. A total of about 15 stories were recorded. Only 7 of them are used in this paper. People who tell these stories do so with specific skills that make you feel the force of it in the glittering of their eyes.

To find out to what extent the stories told by local people will influence the conservation attitudes and behaviours of people living in urban areas, some of the stories collected from the field were recited to people living in Yaoundé, the capital city of Cameroon. Twelve people attended this session from assorted backgrounds (civil service, NGOs, teachers, churches etc.).

Stories Collected

Story 1: In my youth (1945-1952), people were not afraid of gorillas and gorillas were very gentle creatures. We usually observed gorillas feeding freely on plantains and bananas pith and fruits even in the presence of humans. At that time, gorillas even played with young children who accompanied their parents to the farm. All of this friendly relationship was reversed when some village people started hunting gorillas for meat. The gorilla since then has been very fearful of humans and vice versa.

Story 2: When a gorilla is killed, it is carried to the palace and the gong is played to summon everybody. Everyone gathers in the village singing songs of praises and bravery to the hunter and his father. This choral chanting is referred to as "nguh" (Fossimondi) or "sombo" (Bamumbu). The meat is distributed among the sub-chiefs and notables of the chief, with each of them receiving a pre-designated part of the animal. In some communities the hunter is rewarded with a traditional title "somgwei". In some communities he is rewarded with hunting cartridges. The heart is kept by the chief so that, in case the gorilla in question was the totem of someone in the village, the heart together with some other herbs will be used to disconnect him/her from the killed totem so that they can survive…

"Women of child bearing age will not eat gorilla meat because if they do so they will either be barren or give birth to gorilla-like babies".

Story 3: When I was young (referring to some 10-15 years ago) a hunter in a neighbouring village (Fossimondi) shot and killed a male gorilla while hunting. It happened that this gorilla was the totem of the most powerful herbalist in our village. Since he could not survive without his animal totem, he died. We have not - and will never have - such an effective and helpful herbalist in this village. Because of this, I want all gorillas to be saved. Two years ago a gorilla raided my farm and destroyed my plantains but I forgive them because that is their own way of finding food. Killing gorillas means taking away very important people from my village and I am totally against it.

Story 4: While walking on all fours, the gorilla hardly uses its left hand. The gorilla's left hand is the most powerful of its limbs. The gorilla itself treats this hand with a lot of respect. It is called the "chieftaincy" hand because herbalists who use gorilla totems to harvest herbs do so only with its left hand. Owners of gorilla totems must avoid using their left hand while fighting because if they do, the victim may go unconscious or even die from a slab with the left hand. This is why the left hand bone of a gorilla is used for medicine.

Story 5: I am a hunter; I want gorillas to be protected because they assist me in the forest. While foraging gorillas create forest tracks that facilitate movement of hunters at night. Also when I am hungry in the forest I eat anything that gorillas have fed on. So I believe gorillas like our ancestors direct me when I am out there in the forest.

Story 6: Two years ago I went hunting; it was 3:30 pm and I left my hunting hut to go look up for some monkeys I heard calling. I was accompanied by my favourite dog named "Whisky". Just a few minutes from camp, I arrived at a hill. Suddenly my dog ran to me with some frustration as if it was running away from something frightful. I looked up and saw a big gorilla sitting and feeding on some leaves on the hunter's trail I was moving on. I was frightened at first from the sight of the animal's size. But the gorilla was just sitting there undisturbed and where it was sitting was the only accessible path on that hill. So I mentioned these words in my dialect "pass go side whei you want go make I come pass my own. No bi you one get this forest." Meaning "you do not own this forest alone; go your own way so that I can also pass and continue my journey". Immediately the gorilla moved across the hill towards the left. I then continued my journey with my dog undisturbed.

Story 7: The gorilla said that it was the strongest and most powerful animal. Another animal told the gorilla that what he believes is not true. It advised the gorilla to go stand by the roadside if it intended to see the strongest of all animals. The gorilla feeling challenged agreed to go see this challenger. So it went and hid itself in the bush beside the roadside. Soon it saw a man moving along the road with something in his hand (a gun) which the gorilla thought was a stick. As the man was approaching, the gorilla leapt out of the bush without delay to confront the man. The man shot the gorilla and since this day, man (the hunter) is most powerful.

Interpretation of the Stories

The second story seems to suggest that that the villagers rarely killed gorillas in the past and when they did there was a reason. This shows the respect people had for these human-like creatures. When he says the hunters are rewarded, what comes to my mind is a man being rewarded after defeating a co-human at war. Hunting of gorillas was sacred and imbued with a lot of myths and superstitious beliefs, so much that the hunter needed not only physical braveness but spiritual and transformative powers. As the first story suggests, when outsiders came in with guns, the balance did change. Since gorillas could now be killed with a wave of the hand and sold for money, the kinship is lost, there are no more rewards for bravery and this tradition is finished.

We did hear countless stories about gorillas being used as totems and the use of totems by herbalists to collect medicinal herbs. In a society where western "modern" medicine does not exist, the significance of these beliefs should not be underestimated.

As the lady in the third story narrates, it is very clear that killing a gorilla that has a spiritual connection to traditional medicine men can bring grief to an entire community. Can this belief therefore serve as a motivation to protect gorillas? Another lesson from this story (3) is the expression of kinship with gorillas as used in the word "forgive". She realizes that, by cutting down forest for farmland, man has done harm to these apes and raiding of crops is not intentional but it is carried out in response to lack of alternatives. Her willingness to forgive gorillas that destroy crops, because she believes that if a gorilla is killed people will die, shows the extent to which totemic beliefs can influence people's behaviours in this area.

While stories 4 and 5 come back to the power and trust which have been mentioned above, story 6 brings in another new theme, that of mutual understanding. Gorillas and humans (hunters) can communicate and act in mutual consent for each other's benefit. This story raised a lot of discussion when retold. Do gorillas understand human language or intentions? Story 7 demonstrates dominance of humans over gorillas. As the story suggests, this is because humans can use guns.

Urban Interventions: Yaoundé Comments and Discussions

When we recited stories told in the villages at the session in Yaoundé it provoked a lot of comments and heated debates, and also opened the way for more stories of the same nature to be shared. Below are some of the participants' reactions to numbers 3 and 6.

Story 3:

- According to my own thinking, if gorillas raid crops they should be treated as the worst enemies. In this regard, I do not understand why the woman in the story shows so much passion to this animal.

- I believe the woman values human beings more than crops and since she has that strong totemic belief that a man will die if a gorilla is killed, she will rather have her farm raided than have a fellow human killed.

- What is interesting to me is the fact that this woman kind of connects gorillas with the population of the village.

- One other reason someone pointed out was that this woman could tolerate gorillas raiding her farm because of the belief that if a gorilla defaecates on your farm you will have a good harvest that year and in the years to come.

- Someone remarked that less tolerant or more tolerant as in the story might just have been human nature.

- Someone asked the participant from the religious organisation if he believed in the story or totemic beliefs and he answered: "It is not easy to be an African and a Christian at the same time because the power of the totemic beliefs is too strong to be ignored. Although I believe that gorillas are used as totems, as a Christian I do not care about it."

- Inspired by this story one other participant narrated a story he knew from his own village which goes as follows: "A man pleaded to a chimpanzee/gorilla hunter that when he sees a group of gorillas in the forest, he should not kill the one with the bald head. Unfortunately this hunter shot dead the bald headed gorilla. A bigger one sprang out of the bush and tortured the hunter severely. The totem owner died. But the hunter survived." Two other participants confirmed that they had heard the same story.

Story 6:

- The first reaction was a question that was asked by one of the participants as to whether gorillas understand local languages.

- Someone else was concerned about the gentleness of the gorilla. He said that the gorilla as the story portrays can tell if you want to be friendly or if you want to kill it. He said this is contrary to the view he had about the gorilla which is that it is a dangerous animal and should be feared. He now has the opinion that the gorilla is like humans, the only difference being that it lives in the forest.

- A lady said that she was advised not to buy ape meat in a market in Yaoundé when she was pregnant in the belief that, if she does, her baby would look like an ape. She changed her intention and went for an alternative. Much time was spent on this story because it had a lot of meaning and implications for traditional tales of this nature.

Conclusions

Stories about gorillas when recorded or when recited can generate a lot of interest. They provide a wonderful opportunity to initiate conservation education and have a lot of value when people perceive them as coming from their communities. These stories are filled with life and one does not need to believe in them to feel their power. Yet they are full of mysteries and contradictions. Either you kill gorillas because they raid crops or you adore them because your grandfather uses them as totems. Either you kill a gorilla to be given an elevated title (chieftaincy titles are given to brave hunters who kill gorillas in some stories) in the community or you save them it because they are used by a herbalist to harvest medicinal plants. Different culture systems give rise to different levels of tolerance, acceptance or rejection. Whatever it is, I believe - and strongly - that it is within these contradictions that the conservationist must work to find solutions to the problems facing our close relatives. If we allow these rich cultural restraints against hunting and eating gorillas to continue to wane, the levels of intolerance and persecution will become more frequent in the near future.

Denis Ndeloh Etiendem

References

Colding, J. & Folke, C. (2001): Social Taboos: 'Invisible' Systems of Local Resource Management and Biological Conservation. Ecological Applications 11 (Part 2): 584-600

Jacobson, S. K. et al. (2006): Conservation Education and Outreach Techniques. Oxford (Oxford University Press)

Nkembi, L. et al. (2006): Lebialem Highlands Great Apes Conservation Programme: Mid term Progress Report to Forestry Bureau, CoaTaiwan. Menji, Environment and Rural Development Foundation (ERuDeF), 32

Oates, J. et al. (2007): Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of the Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli). Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria, 40

Rose, L. A. et al. (2003): Consuming Nature: A photo Essay on African Rain Forest Exploitation. California (Altisima Press)