Carrying Capacity of the Virunga Massif for Mountain Gorillas

Categories: Journal no. 71, Gorilla Numbers, Censuses, Ecology, Behaviour, Rwanda, Mikeno, Mgahinga, Volcano National Park

The Virunga Massif, a chain of volcanoes in the heart of Africa, is home to one of two remaining populations of the endangered mountain gorilla. Six dormant volcanoes tower to elevations of up to 4,500 meters and span just 450 km² across three countries - the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, and Rwanda. Its complex geographical structure creates a diverse mosaic of habitat types, supporting a variety of fauna and flora. Here, mountain gorillas live in a protected habitat surrounded by the highest human population densities in sub-Saharan Africa.

How many mountain gorillas can the Virunga Massif truly sustain? It is a question we hear often - from conservation partners, researchers, and visitors who stand in awe of these forests. Scientists call this concept carrying capacity, the idea that every ecosystem has a limit to the number of individuals it can support over time, based on the availability of food, space, and other critical resources. Understanding this limit is not just theoretical; it plays a key role in how we measure the impact of conservation efforts and set realistic targets and expectations for long-term population management.

In the 1990s, researcher Alastair McNeilage (1995) was the first to tackle the challenging task of estimating how many gorillas the Virunga Massif could support. Using information about the types of habitats within the forest and how gorillas use these spaces, he estimated that the population would eventually reach carrying capacity once it passed a benchmark of around 600 individuals. That threshold has now been crossed.

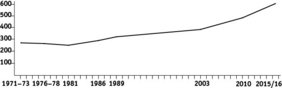

Thanks to decades of intensive, long-term collaborative conservation efforts, the Virunga gorilla population has steadily grown and recovered from a low of just ~250 individuals in the 1980s to more than 600 (639-669) gorillas in 2015/16 (Granjon et al. 2020). But now, new questions arise. Has the Virunga gorilla population already reached its limit, given the forest's small size and geographic isolation? Or could it still support more gorillas? And if they are nearing the limit, what ecological or behavioural factors will begin to slow, or eventually halt, this remarkable growth?

McNeilage (1995) highlighted key ecological and social mechanisms that could regulate the size of the Virunga gorilla population and emphasized the need for more research into how these factors play out in real time. For example, he proposed that human disturbance could affect gorilla movement and increase mortality; that limited food availability could spark intra-specific food competition, lowering birth rates and further raising mortality, unless gorillas can adapt to new resources; and that social pressures, such as more frequent interactions between groups and solitary males, could lead to increased infanticide and stress, both of which suppress population growth.

Since McNeilage's study (1995), long-term monitoring has significantly deepened our understanding of the forces that shape gorilla population dynamics in the Virungas. Thanks to continuous records dating back to 1967, when Dian Fossey established the Karisoke Research Center between Mount Karisimbi and Mount Bisoke in Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda, researchers have been able to track the changes in gorilla social behaviours, reproduction, and movement over decades. After her death in 1985, the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund (i.e., the Fossey Fund), named in her honor, together with its conservation partners, carried forward this legacy.

A primary focus of the Fossey Fund's efforts has been to continue the long-term monitoring and scientific study of gorillas in the Karisoke research area, representing today's descendants of the gorilla social groups originally studied by Fossey. With data spanning nearly six decades, this represents one of the world's longest-running primate research projects, providing unparalleled insights into factors that influence population dynamics in a wild primate population living in restricted habitat.

From the 1980s until around 2010, gorillas in the Karisoke research area experienced the highest growth rates of any region in the Virungas (Gray et al. 2013). But more recently, this subset of the population has experienced slower growth rates, offering a rare chance to investigate the underlying biological and social mechanisms that might be regulating population size and structure (Caillaud et al. 2020, Morrison et al. 2022).

From the early 1990s to 2006, the Karisoke subpopulation consisted of three stable gorilla groups that grew steadily. These groups reached sizes up to 65 gorillas, containing up to 8 silverbacks - the largest groups ever recorded for gorillas. But stability did not last. Young males matured and began challenging the aging silverbacks for leadership, triggering a cascade of group splits and new group formations starting in 2006. Within just a few years, group density in the Karisoke research area tripled, while home range expansion into adjacent areas remained limited and slow. This sudden reorganization reshaped the social fabric of the Karisoke subpopulation, introducing new risks and pressures that continue to influence gorilla behaviour and survival today (Caillaud et al. 2020).

Since 2006, the presence of more gorilla groups inhabiting the same area has led to an 11-fold increase in home range overlap between neighbouring groups, triggering a 3-fold rise in inter-unit encounters (i.e., interactions between an established social group and either a solitary male or another social group) (Caillaud et al. 2020). These encounters can be highly aggressive and sometimes result in fatal injuries. As a result, the rate of infanticide rose 4.5-fold, and adult males, the primary defenders of their groups, faced an increased risk of dying from severe injuries (Caillaud et al. 2020). Notably, the rise in infanticide alone accounted for 57 % of the decline in population growth observed in the Karisoke subpopulation between 2000 and 2017 (Caillaud et al. 2020).

At the same time, more frequent encounters also created more opportunities for females to transfer to neighbouring groups or accompany solitary males. Female transfers increased 10-fold under these conditions (Caillaud et al. 2020). A recent study by Robin Morrison et al. (2023) showed that such transfers delay reproduction: females who transfer once between births experience interbirth intervals that are 7.5 months longer than those who remain in the same group, and this delay grows to 18 months for females who transfer twice. These delays have further contributed to the observed slowing of population growth.

In contrast to these pronounced social effects, long-term data from the Karisoke subpopulation lend little support for the idea that intra-specific food competition currently limits female reproductive success. While average interbirth intervals have lengthened in recent years, this trend appears to be primarily driven by delays among females who transfer between groups (Morrison et al. 2020). So far, there is no evidence that Virunga mountain gorillas are facing reduced food availability, even as gorilla densities have increased. However, rising food competition cannot be ruled out in the future, especially as the population continues to grow and as more attention is given to lesser-studied regions of the Virunga Massif beyond the historical Karisoke research area.

Since 2019, the Fossey Fund, in collaboration with the Rwanda Development Board, has expanded its research efforts to include eight gorilla groups outside the historical Karisoke research area. Six of these groups range in forest areas that experienced little to no population growth until 2010 but have recently begun to show encouraging upward trends. Data from this research expansion initiative revealed striking dietary differences between groups across Volcanoes National Park, a finding that aligns with the diverse habitat types where these groups range (Ihimbazwe et al. 2025). Researchers have now documented 57 additional food items in the Virunga mountain gorilla diet (Ihimbazwe et al. 2025), highlighting the need for updated assessments of food biomass and nutritional quality, which are critical components for estimating carrying capacity. These findings also reinforce earlier studies demonstrating the impressive dietary flexibility of mountain gorillas. Such flexibility may buffer the population from the effects of food competition by allowing gorillas to shift to alternative resources as availability changes. Still, we cannot rule out the possibility that food competition plays a critical role in regulating population growth in these newly studied areas. The timing and influence of each regulatory factor may differ by forest area and may depend on local habitat characteristics.

The question of carrying capacity becomes even more complicated when viewed in the broader context of the ecosystem. Mountain gorillas are not the only large herbivores inhabiting the Virunga Massif. They share the forest with elephants, buffalo, bushbucks, and duikers. For this reason, carrying capacity should not be assessed in isolation, and inter-specific competition must be considered. These sympatric herbivores also benefit from gorilla conservation measures, as highlighted in the most recent large mammal survey in Rwanda's Volcanoes National Park led by a young researcher from the Fossey Fund, Jean Claude Twahirwa and his team (2025). Andrew Plumptre's research (1991) in the 1990s found limited dietary overlap between mountain gorillas and other large mammals in the historical Karisoke research area. However, little is known about the diets of these species across other parts of the Virunga Massif.

It is likely that the feeding patterns of other herbivores, like those of the gorillas, vary substantially across space. To fully understand carrying capacity, we need a better understanding of how the diets of gorillas and sympatric herbivores overlap across time and the landscape, an essential piece of the carrying capacity puzzle.

Adding to the complexity of estimating carrying capacity is the simple fact that neither gorillas nor humans live in a static world. Human population growth and climate change are rapidly reshaping ecosystems, including those that mountain gorillas call home. The density of people living around gorilla habitats continues to rise, placing growing pressure on natural resources. One ongoing threat is the presence of snares set by poachers across the Virunga Massif which remains a significant conservation challenge. Though intended for other wildlife, these traps can injure or kill gorillas. Ongoing research is exploring how encounters with snares may influence gorilla ranging patterns, another important factor in estimating their carrying capacity.

Another key density-dependent factor that may limit future population growth has long been underrecognized: infectious disease. Compelling evidence stems from a recent, collaborative parasitological study conducted across the Virunga Massif (Petrželková et al. 2021, 2022, Mason et al. 2025). Conservationists have noted a rise in severe gastrointestinal illness within forest areas that experienced the highest population growth up to 2010, encompassing the Karisoke study area. Analyses of historical fecal samples show that over the past two decades, Hyostrongylus, a stomach parasite commonly found in pigs, has become dominant within the gorilla parasite community in this forest region (Mason et al. 2025). This shift coincides with a peak in gorilla group density and the social changes that followed.

Non-invasive endocrine studies have shown that encounters between gorilla social units can elevate stress levels up to eight times compared to baseline. Such spikes in stress may compromise immune function, increasing vulnerability to disease. However, stress is likely not the only contributing factor. For example, environmental characteristics exacerbated by climate fluctuations may create more favorable conditions for the development and survival of infectious larvae, leading to higher parasite exposure and infection rates. Additionally, denser gorilla populations may increase environmental contamination, heightening the likelihood of re-infection with parasites shed in gorilla feces. This study also revealed significant spatial variation in the load of strongylid eggs, a common proxy for infection intensity, across the Virunga Massif, with infection patterns closely tied to habitat types and differences in historical population growth patterns (Petrželková et al. 2021, 2022).

Thanks to decades of long-term monitoring, we now have a much clearer understanding of the factors and mechanisms that regulate the growth of the mountain gorilla population. This growing body of empirical data will be essential for refining future models that revisit and build on McNeilage's (1995) original estimates of carrying capacity. These models must account for the Virunga Massif's geographical complexity and how it shapes gorilla ecology, social dynamics, health, and demographic trends. Future projections would also benefit from the continued research efforts outlined throughout this article, such as updating biomass estimates based on the expanded list of gorilla food items, assessing nutritional quality, and investigating interspecific food competition.

Crucially, these research efforts must further extend beyond the historical Karisoke research area and Rwanda, which has been the foundation of much of our current knowledge of Virunga mountain gorillas. Expanding research into understudied forest areas in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda is vital for improving the accuracy and generalizability of carrying capacity estimates. As long as models rely primarily on data from Rwanda, they will remain limited. This underscores the importance of continued strong transboundary collaboration in future research and conservation planning.

Looking ahead, Rwanda's commitment to restoring parts of Volcanoes National Park, areas that were converted into agricultural land between the 1950s and 1970s, represents a major opportunity. Park restoration will not only increase available habitat for gorillas but may also help alleviate the social pressures and rising mortality rates associated with higher group density. Models of carrying capacity can no longer ignore the impact of forest regeneration along the park boundaries. Long-term ecological monitoring of these restoration areas will be critical for tracking the recolonization of fauna and flora, including gorillas and their key food plants.

So where does the Virunga mountain gorilla population stand today, a decade after the last survey? Due to disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and regional unrest, the standard five-to-seven-year interval between population surveys has lapsed. Still, there is growing optimism that planning for the next transboundary survey can soon resume and will provide further insights into the population, now amassing over 600 individuals.

As forest restoration efforts take hold, growth rates may rise again in the coming decade. But the long-term trajectory is clear: growth cannot continue indefinitely. At some point, the Virunga mountain gorilla population will reach its ecological maximum. Future models for estimating carrying capacity will help conservationists set realistic targets for what that maximum might be, and, just as importantly, what it will take to sustain it.

When that time comes, the definition of conservation success will evolve. The goal will no longer be growth, but stability. And achieving that will require the same commitment, collaboration, and vigilance that made the population's recovery possible in the first place, if not more, in this rapidly changing world.

The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund

References

Caillaud, D. et al. (2020): Violent encounters between social units hinder the growth of a high-density mountain gorilla population. Science Advances 6, eaba0724

Twahirwa, J. C. et al. (2025): Positive population trends among meso- and megaherbivores follow intensive conservation efforts in Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda. Wildlife Biology 2025 (1), 1-10. doi.org/10.1002/wlb3.01118

Granjon, A. C. et al. (2020): Estimating abundance and growth rates in a wild mountain gorilla population. Animal Conservation 23 (4), 455-465

Gray, M. et al. (2013): Genetic census reveals increased but uneven growth of a critically endangered mountain gorilla population. Biological Conservation 158, 230-238. doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.09.018

Ihimbazwe, H. et al. (2025): Dietary Variability Among Mountain Gorilla Groups Across Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda. Ecology and Evolution 15 (5), 1-20. doi.org/10.1002/ece3.71192

Mason, B. et al. (2025): Untangling parasite epidemiology of mountain gorillas through historical samples: Strongylid nematodes are friends or foe? Biological Conservation 310. doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2025.111319

McNeilage, A. (1995): Mountain gorillas in the Virunga volcanoes: ecology and carrying capacity. University of Bristol

Morrison, R. E. et al. (2023): Cascading effects of social dynamics on the reproduction, survival, and population growth of mountain gorillas. Animal Conservation 26 (3), 398-411. doi.org/10.1111/acv.12830

Petrželková, K. J. et al. (2022): Ecological drivers of helminth infection patterns in the Virunga Massif mountain gorilla population. International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife, 17 (November 2021), 174-184. doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2022.01.007

Petrželková, K. J. et al. (2021): Heterogeneity in patterns of helminth infections across populations of mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei). Scientific Reports 11 (1), 1-14. doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89283-4

Plumptre, A. J. (1991): Plant-herbivore dynamics in the Birungas. Bristol University, UK