The Relationship between an Indigenous Batwa Population and their Ancestral Forests in Kahuzi-Biega

Categories: Journal no. 71, Rain Forest, Mining for mineral resources, Conflicts, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kahuzi-Biega, Grauer's Gorilla

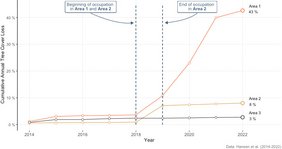

Cumulative tree cover loss in three areas of Kahuzi-Biega National Park between 2014 and 2022. Area 1: continual occupation by groups of Batwa from October 2018 to the present day. Area 2: temporary occupation between October 2018 and September 2019. Area 3: no Batwa occupation. (© Simpson et al. 2024 nach Hansen et al. 2010-2022)

What is the role of indigenous people in conservation? Are they 'forest destroyers' or 'forest protectors'? Both narratives argue that the fate of nature ultimately hinges upon indigenous peoples. This paper challenges this viewpoint, by showing that the narratives divert attention from the structural dynamics at the root of environmental change. Moreover, these narratives, representing indigenous people in simplified ways, feed into differing visions of conservation that ultimately fail people and nature.

When the Kahuzi-Biega National Park in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) was established, an indigenous group known as the Batwa were forcibly expelled from their ancestral lands inside the park during the 1970s. For them the impact of this expulsion was dramatic: they were left landless, pushed to live an impoverished existence among other communities outside the park, without land titles or financial compensation. From October 2018 onwards, however, the descendants of these Batwa started to reoccupy parts of the park. The park authorities and the national army responded with heavy-handed militarized conservation approach, in their attempts to expel the Batwa from the park once more. Throughout and after these events, competing narratives emerged which depict the Batwa's relationships to nature.

For our study, we combined quantitative and qualitative data. We analysed satellite images and data on tree cover loss. The qualitative component of the research is based on fieldwork from 2019 to 2024. During multiple trips, we conducted focus groups, semi-structured interviews, transect walks, and detailed field observations with people living in and around the park's highland sector. We spoke to Batwa and the members of other social and ethnic groups living in the area, customary and state authorities, farmers, artisanal miners, charcoal and timber producers and traders, non-state armed groups, park guards, and soldiers from the government military, among others.

Stories of forest destroyers and forest guardians are deployed by actors with different views about the role of the state and indigenous peoples in conservation. On the one hand, the forest destroyers frame serves a hegemonic function, naturalizing state control of people, territory and nature as unquestionable common sense. On the other hand, the forest guardians narrative naturalizes indigenous peoples' rights to their ancestral lands, as part of a counter-hegemonic struggle against state governance of nature. The narratives promoted by the discourse coalitions place the Batwa at the epicenter of the events - either as unnecessarily victimized protectors of nature, or as victimizing perpetrators against whom nature needs to be protected. Our data challenge the narrative framings deployed by the two coalitions.

In October 2018, after multiple promises to provide them with land outside the park were broken, groups of Batwa started to return to the park's highland sector, to two main regions, respectively overlapping with the territories of Kalehe and Kabare. Once inside the park, they created new settlements with traditional houses, farms, churches, and schools. This event provoked diagonally opposed reactions from the different discourse coalitions. On the one hand, the park authorities accuse the Batwa of destroying the park; and on the other hand, indigenous rights NGOs either deny or downplay these claims.

We assessed the impact of the Batwa's presence on tree cover inside the park with satellite data in three areas of the park. Areas 1 and 2 were those to which the Batwa returned, area 3 was a control area. The extent of tree cover loss in all three areas was relatively low between 2010 and 2017 as well as in 2018. However, the situation changed dramatically in 2019, just after groups of Batwa had started returning to the forest. Area 1 experienced 1,602 ha tree cover loss and area 2 experienced 536 ha tree cover loss between 2019 and 2022. In area 2, 466 ha of this loss occurred in 2019. This was reduced from 2020 to 2022 when they left this region again. Area 3, which is not affected by the Batwa's return, experienced just 22 ha tree cover loss over the entire period 2019-2022. In sum, satellite data suggests the presence of the Batwa significantly accelerated rates of tree cover loss.

However, extensive field research reveals a much more complex reality. The Batwa surrounding Kahuzi-Biega National Park are among the most marginalized groups in the region. They suffer from nutritional deficiencies, poor hygiene, lack of medical care, inadequate housing, a high mortality rate. Where compensation has been provided, it has been limited, and mostly captured by Batwa elites. This marginalization has severely constrained the livelihood options available to most of the Batwa.

Since returning to the park, the Batwa have been able to take advantage of livelihood opportunities provided by wider structural conditions: in particular, massive demand for the park's charcoal and timber resources from the nearby cities of Goma and Bukavu.

In this respect, the Batwa employ two strategies. First, various Batwa chiefs have positioned themselves as the gatekeepers to a wider commodity chain leading to the park, which brings together a multitude of state and non-state actors. Second, to maintain control of this position within the commodity chain, and access to the park's resources, they resorted to violence; at times collaborating with, at other times contesting, different armed actors. Batwa chiefs were selling access to the park to neighbouring Bantu communities. During an interview with a Batwa chief, a steady stream of traders was coming out of the park, carrying planks of wood and sacks of charcoal. The goods were then collected by motorbikes and small pick-up trucks and transported to larger towns. However, the positionality of the Batwa in the commodity chain needs to be contextualized: they are but one, relatively minor, actor among a broader constellation of actors that is driving tree cover loss. Various actors profit from this commodity chain: local entrepreneurs organizing the transportation of goods via boat and trucks from the villages and markets at the edge of the park to Bukavu and Goma; and state agencies including the government military as well as customary authorities and nonstate armed groups extort taxes at different steps along the chain. There are also reports of more senior state officials profiting from the park's resources, in particular through gold mining. This sometimes happens in collaboration with armed groups - showing how state institutions can have ambivalent effects on dynamics of conservation and/or extraction.

As a second strategy, some Batwa chiefs and groups have resorted to violent means to maintain their economic interests and secure territory inside the park. For instance, a group of armed Batwa attacked the ICCN's Lemera patrol post Kalehe territory - park authorities claim this was done in collaboration with the Mai Mai Cisayura - on 2 August 2019. A park guard was killed during the attack. As a result, ICCN abandoned the patrol post entirely, which made it possible for the Batwa, in collaboration with other communities, to more easily access, extract and sell the park's resources.

Other than with park guards, the Batwa have ambiguous and contentious relations with a range of armed actors. Historically, various rebel groups have been also involved in illegal resource extraction within the park. The Batwa's return to the park's highland sector in 2018 coincided with the further (re)mobilization of armed groups that took advantage of the opportunity to enrich themselves. These groups were organizing and taxing the extraction and trade of the park's minerals; and, to a lesser degree, timber and charcoal. Several groups established bases in the park to profit from its resources, exacerbating insecurity in the surrounding area. The Batwa of Buhoyi village briefly worked alongside the Mai Mai Cisayura to secure territory inside the park in the latter half of 2019. On other occasions, Batwa have been victimized by non-state armed groups. One group killed a Batwa man and injured six others when its soldiers attacked a Batwa village inside the park in 2024.

Based on our study, we challenge idealized depictions of indigenous peoples as either protectors or perpetrators, advocating instead for a context-dependent view of their role. Narratives portraying the Batwa as forest destroyers justified a heavy-handed approach to conservation law enforcement, involving joint-operations by the park guards and the military. Human rights abuses committed during these operations triggered international outrage, which was ultimately counter-productive for the park authorities. On the other hand, the forest guardians narrative renders invisible the Batwa's agency in deforestation and violence against park guards and government soldiers. Nuancing both narratives, we propose that the Batwa - much like the park guards - should be viewed simultaneously as victims and perpetrators, entangled in the broader dynamics of violence and extraction. This allows for cases where indigenous peoples are indeed exemplary environmental stewards - as much recent research and policy literature suggests - while also accounting for more complex situations where they play by rules of games that prioritize resource extraction, leading to ecological degradation.

Original publication

Simpson, F. O., Titeca, K., Pellegrini, L., Muller, T. & Dubois, M. M. (2024): Indigenous forest destroyers or guardians? The indigenous Batwa and their ancestral forests in Kahuzi-Biega National Park, DRC. World Development 186, 106818