Law Enforcement in Itombwe Reserve

Categories: Gorilla Journal, Journal no. 57, Protective Measures, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Itombwe, Grauer's Gorilla

Conservation approaches in the Democratic Republic of the Congo have evolved from fine and fences, top-down approaches to adaptive co-management approaches (Inogwabini 2014; Pelissier et al. 2015; Kujirakwinja et al. 2017, 2018). Communities were excluded in conservation interventions such as law enforcement interventions. They were merely targeted and identified as poachers and associated with degradation of forests and species depletion (Oates 2002; Moreto & Lemieux 2015). With incoming changes on the ground and globally, innovative models have been implemented to preserve protected areas, especially in countries where protected area agencies are weak and lacking financial and technical capacities (Borrini-Feyerabend et al. 2004; Berdej et al. 2015). Although changes have been implemented, law enforcement interventions have been and are still conducted by armed rangers supported by armed forces (Marijnen 2017).

With changes in the governance of protected area conservation practitioners have questioned the exclusive patrolling approach for protected areas that have been created through participatory approach such as Itombwe (Kujirakwinja et al. 2018). Since its gazettement, the management of Itombwe has established community governance committees as a way of involving community representatives in the management of the reserve. Moreover, to respond to management challenges and ineffective management of the reserve, community members and their leaders have been involved in various conservation activities either to support ongoing interventions or to lead some of the interventions.

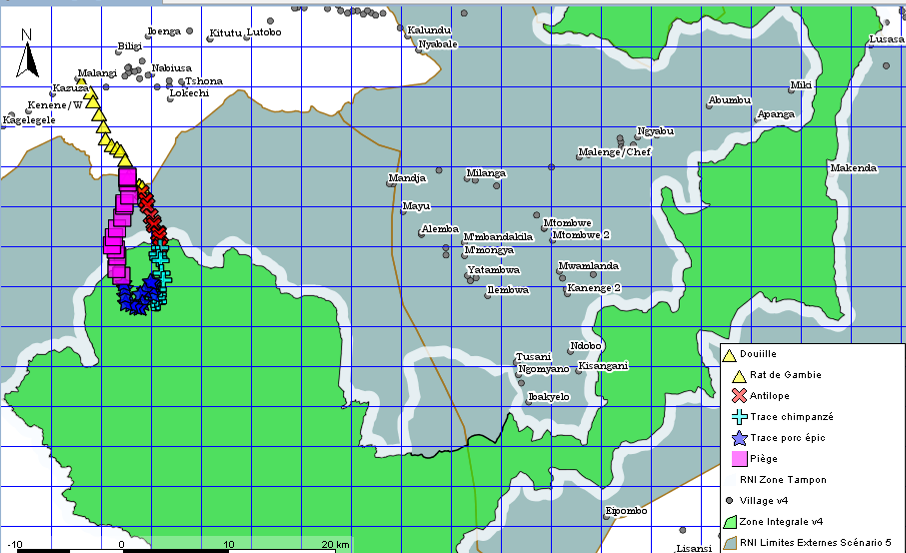

Management approaches in Itombwe are being adjusted to fit collaborative processes. Although armed rangers are still involved in patrolling some areas of the reserve, communities have been tasked to patrol areas located in management zones surrounding their villages. The process is based on established community governance structures, local agreement for community monitoring, training and patrols in key zones. As a result, patrol coverage of the reserve has increased compared to the previous year.

Law Enforcement Approaches in DRC

Protected areas in DRC are a legacy of colonization (Harroy 1993; Van Schuylenbergh 2009; Pouillard 2016). Most protected areas were created during that time based on restrictions for local communities. The fine and fences approach has been implemented since then and restrictions to resources are still being implemented in one or another way despite the existence of some collaborative approaches and processes.

Based on the DRC Conservation Law 014 (Journal Officiel 2014), ecoguards are authorized to carry guns for patrolling and are empowered to make arrests and defend themselves in case of any gun exchange with poachers and other armed forces that threaten their work and lives. In various places, there have been attempts to include communities in either scaring animals from villages to force them going back in the forest (e.g., Virunga Massif with Human and Gorilla - HUGO).

Towards Involving Local Communities in Law Enforcement Interventions in Itombwe

Itombwe Nature Reserve (NR - Réserve Naturelle dʼItombwe, RNI) was legally established in 2006 and its boundaries validated by the governor of South Kivu in 2016 as a result of a wider involvement of stakeholders. It covers about 6,000 km with less than 50 rangers and inadequate funding (see Baruka 2015). Baruka found that the Itombwe Nature Reserve has been underfunded by about 80 % of its need in 2015. It is one of the strongholds of remaining Grauer's gorilla (Gorilla beringei graueri) in the world. Unfortunately, this species along with others (chimpanzee, elephant, etc.) are threatened by traditional and armed poaching, mining and habitat fragmentation by agriculture and cattle husbandry (Plumptre et al. 2016; Spira et al. 2017).

To face the challenge of patrolling that area with inadequate financial support, in agreement with local established community governance structures, community members have been trained to conduct patrols and support other interventions such as boundaries demarcation.

The process of establishing patrolling groups included:

- Operational agreement between ICCN and community committees for patrolling. Itombwe NR has 6 community governance committees established. They are the foundation of the community approach as interface to ICCN in respective communities, this is based on the current community conservation strategy (ICCN 2015).

Committees are selected based on the prioritized sectors based on the presence of conservation targets, especially gorillas (Gorilla beringei graueri). Once committees are selected, an agreement is signed between ICCN, communities and financial supporting NGOs - international and national NGOs. The agreement specifies key activities, results and timeframe - Selection of community. The selection of scouts by local governance structures based on agreed criteria such as be able to read and write, be fit, be able to learn and use field equipment such as GPS, smartphone for data collection using cybertracker application,

- Training of selected community scouts. Selected community scouts are trained by senior rangers and wardens for data collection based on the ICCN data collection protocol.

They don't undergo military training. Their main role is ecological monitoring (species and human activities) as well as to report illegal activities. In circumstances where they move with rangers, offenders are arrested by the rangers based on existing laws. - Patrols and reporting. Community scouts are equipped with necessary equipment for data collection. They collect data on wildlife species they see and human activities as well as any ecological feature that could inform management on changes or strategies.

Data collected by rangers are sent to the park headquarters and entered into the computer using the SMART (Spatial Monitoring And Reporting Tool) that archives and analyzes patrol data for DRC protected areas. - Information sharing. Once data are analyzed, results are shared with communities during their meetings for further actions on the ground. Moreover, they are used to plan for future patrols with communities.

Lessons learned

- Trust building and collaboration. The ongoing community patrolling has revived trust and confidence between communities and conservation bodies as they are involved directly in conservation activities.

- Increase patrol coverage and protection of conservation targets. The involvement of communities in patrols has leveraged low number of rangers to cover the reserve. Therefore, communities have covered areas that could not have been covered by rangers because of insecurity. Local communities know the area and all the trails better than the rangers.

For example, in April 2008 community scouts arrested a poacher with a hunting gun. The poacher was reported to local authorities and ICCN. - Resource sharing. By signing agreements with communities and financing patrols, they gain some stipends that support their households. It has been seen as a way of sharing conservation money with communities.

- Practical awareness. The involvement of community scouts in patrolling the reserve has echoed the openness of ICCN to co-management and support to communities. In a workshop, one representative from communities said that the approach should be expanded to other areas.

Conclusion

Conservation management practices have evolved to include various stakeholders at different levels to curb anthropogenic threats to key species. In Itombwe, the community patrolling practices have been tested and prove that it is possible to work with communities for long-term conservation. However, there are some challenges to be considered as the approach is still at experimental stage:

- the sustainability of the approach given that it is donor supported,

- jealousy and conflicts within the communities,

- conflicts of interest between ecoguards and community scouts,

- complicity between poachers and community scouts for poaching

To respond to these challenges, it is proposed that a detailed practical and operational agreement/manual be developed and implemented by involved parties. But also, the management should ensure that local traditional and political authorities are involved in the enforcement side of the process.

Deo Kujirakwinja, Léonard Mubalama, Jean-Claude Kyungu, Victory Paluku, Gentil Kambale, Félix Igunzi and Jean de Dieu Wasso

Activities for community patrols were funded by WWF, USAID-CARPE, Africapacity, Rainforest UK, Berggorilla & Regenwald Direkthilfe, La Vallée des Singes, RACOD and ICCN.

Selected Literature

Baruka, G. (2015): Analyse des financements des aires protégées en République Démocratique du Congo (RDC). Université Senghor

Berdej, S. et al. (2015): Governance and community conservation. 2. Nova Scotia

Borrini-Feyerabend, G. et al. (2004): Sharing power: learning by doing in co-management of natural resources throughout the world. Tehran (IIED and IUCN/CEESP/CMWG)

Harroy, J.-P. (1993): Contribution à l'histoire jusque 1934 de la création de l'institut des parcs nationaux du Congo belge. Civilisations 41, 427-442

ICCN (2015): Strateégie nationale de conservation communautaire dans les aires protégées de la RDC (2015-2020). Page 56. ICCN, Kinshasa, DRC

Inogwabini, B. (2014): Conserving biodiversity in the Democratic Republic of Congo: a brief history, current trends and insights for the future. Parks 20, 101-110

Journal Officiel (2014): Loi sur la conservation de la nature. Page Journal Officiel de la Républic Démocratique du Congo

Kujirakwinja, D. et al. (2016): Participatory mapping in the Itombwe Nature Reserve. Gorilla Journal 53, 9-12

Kujirakwinja, D. et al. (2018): Establishing the Itombwe Natural Reserve: science, participatory consultations and zoning. Oryx online, 49-57

Marijnen, E. (2017): The 'green militarisation' of development aid, the European Commission and the Virunga National Park, DR Congo. Third World Quarterly 38, 1566-1582

Moreto, W. D. & Lemieux, A. M. (2015): Poaching in Uganda: Perspectives of Law Enforcement Rangers. Deviant Behavior 36, 853-873

Oates, J. F. (2002): Politicians and poachers: the political economy of wildlife policy in Africa. Human Ecology 30

Pelissier, C. et al. (2015): Aires protégées d'Afrique Centrale. Etat 2015. P. 256 in: Doumenge, C. et al. (eds.): Aires protégées d'Afrique Centrale. Etat 2015. Kinshasa, Yaoundé (OFAC)

Plumptre, A. J. et al. (2016): Catastrophic decline of world's largest primate: 80% loss of Grauer's gorilla (Gorilla beringei graueri) population justifies critically endangered status. PLoS ONE 11

Pouillard, V. (2016): Conservation et captures animales au Congo belge (1908-1960). Vers une histoire de la matérialité des politiques de gestion de la faune. Revue histoire 679, 577-604

Spira, C. et al. (2017): The socio-economics of artisanal mining and bushmeat hunting around protected areas: Kahuzi-Biega National Park and Itombwe Nature Reserve, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Oryx online, 136-144

Van Schuylenbergh, P. (2009): Entre délinquance et résistance au congo belge: l'interprétation coloniale du braconnage. Afrique et histoire 7, 25-47